Twenty years earlier as number of Midwest distillers had turned their plants over to a board of trustees who were to control the liquor trade through the kind of monopolistic cartel that had developed in oil, sugar, steel, beef and other commodities. Officially named the “Distillers and Cattle Feeders Trust,” it was popularly known as "The Whiskey Trust.” The organization, based in Peoria, Illinois, gathered in more than 80 distilleries, often using tactics like dynamite to convince holdouts. Most of the plants the Trust procured were shut down. The idea was to control supplies and drive up whiskey prices.

That tactic did not sit well with other American distillers who feared being muscled out of the market. This antipathy was strongest in New York and Kentucky. In 1900 Walter B. Duffy, owner of two distilleries in Rochester, New York, organized a group of three major Kentucky distilleries and five New York alcohol manufacturers into a stock company. The idea was strength in numbers to prevent the Whiskey Trust from threatening them. A chief Duffy ally in this gambit was Henry

Naylon.

Naylon. Naylon like Duffy was a native of Rochester. He was born 1870 into a family of native New Yorkers with ancestral origins in Ireland. Little of Naylon’s early life is recorded but at least one account indicates that he may have been involved in real estate as a young man. That pursuit may have led him into the field of distilling. In the late 1800s the Federal Government had, in effect, shut down several small distilleries in Western New York.

Naylon apparently saw an opportunity, moved to Buffalo, bought three plants and about 1897 consolidated their production under the name, The Erie Distilling Company.

Naylon apparently saw an opportunity, moved to Buffalo, bought three plants and about 1897 consolidated their production under the name, The Erie Distilling Company.Naylon’s first business address was on Genesee near Ellicott but by 1900 he had moved to a spacious five-story building at 141 Seneca Street, shown here. The address also appeared on a cobalt jug produced for him by the Lyons Stoneware Company of Lyons, New York. Naylon’s company adopted a number of proprietary brand names for its whiskeys, none of which the owner bothered to trademark. They

included “Clover Dry Gin,” “Lafayette Special,” “Maryland Flower,” “Orange Blossom,” “Society Cocktails,” and “Yankee Club.” His flagship label was “Erie Club Whiskey,” advertised as “It Is the Best!” As many

included “Clover Dry Gin,” “Lafayette Special,” “Maryland Flower,” “Orange Blossom,” “Society Cocktails,” and “Yankee Club.” His flagship label was “Erie Club Whiskey,” advertised as “It Is the Best!” As many  whiskey men, Naylon gifted favored customers, saloons and public houses featuring his brands. He furnished them with advertising wares such as shot glasses and serving trays featuring Erie Club. For retail customers he provided inexpensive, celluloid-backed pocket mirrors.

whiskey men, Naylon gifted favored customers, saloons and public houses featuring his brands. He furnished them with advertising wares such as shot glasses and serving trays featuring Erie Club. For retail customers he provided inexpensive, celluloid-backed pocket mirrors. Naylon also was having a personal life. In 1881 he married Ellen (called Nellie) A. Corcoran. Like himself, his wife was native-born New Yorker. The 1900 Census found them living in Buffalo with three children, William, 7; Loretta, 5, and Ethel, 4. Henry would take William into his liquor business as the boy matured.

Meanwhile the New York and Kentucky Company, with main offices in Rochester, was thriving while it defied the infamous Whiskey Trust. The capital stock of the company consisted of $1,000,000 in preferred stock and $1,000,000 in common stock, about 25 times that in 2014 dollars. It was paying dividends of 7% on the preferred stock and 6% on common. Moody’s listed the assets as “real estate and appurtenances (conservatively valued at upwards of $850,000), fixtures, machinery, brands and good will of said concerns, all absolutely free from mortgage, debt or other liability.”

One major liability was Walter Duffy, president and organizer of the combine. Duffy ran one of the most notorious whiskey operations in the country, criticized for his outrageous advertising, blasted in the press for shoddy products, and hounded by Federal and state officials for selling his liquor as medicine. [See my post on Duffy, May 1911.] Duffy’s leadership of the New York and Kentucky Company particularly incurred the wrath of Col. E. H. Taylor Jr., considered the Kentucky high priest of straight bourbon. Taylor earlier had lost distilleries through debt to George Stagg, a Kentuckian who was part of the New York and Kentucky Co. Even though a court had ruled 1894 that Taylor’s name could no longer be used in connection with his former distilleries, the ban was ignored by Duffy.

Outraged that someone whom he considered to be so disreputable had come to control his previously owned and prized whiskey operations, Col. Taylor minced no words: There are people who do not know the difference between a jumping-jack and a jackass, and a composite photograph of the two would look so much like him that his nearest friends would call it an excellent portrait of Mr. Walter B. Duffy, President of the "New York and Kentucky Company," owner and great promulgator of “Duffy's Malt Whiskey.”

When Duffy died in 1911, the directors took no time in naming Naylon the president and chairman of the board, likely because of his good business reputation. Henry’s son, William, also was named to the board and eventually would be moved up to the position of corporate secretary. At the same time Naylon was branching out into other enterprises. He was president of Naylon Securities Company and a founding director of the Lafayette National Bank of Buffalo, a member of the Federal Reserve System. He also was a power on the Buffalo political scene and eventually became chair of the Erie County Democratic Party.

During this same period Naylon found his own liquor business in need of expansion and in 1915 he moved to an eight-story building at 154-156 Eagle Street. As shown on his letterhead of that period, not only was he featuring his own brands but had become the sole agent for such national and regional labels as “O.F.C. Whiskey,” “Carlisle,” “McGinnis Rye,” “Walnut Hill,” “Seneca Chief,” and “Burke Hollow.” Naylon’s new quarters were very up-to-date, featuring both telephone exchanges and solid-tire trucks to make deliveries. Naylon issued jugs with the new address.

Increasingly Naylon was being heard as a spokesman for the liquor industry. In a 1916 letter to the Brewer’s Journal, he opined that the lack of revenues from whiskey taxes was shifting the burden of

taxation to real estate and incomes. “Many of the Prohibition States are bankrupt today because the fanatics fear that if their controlled legislatures increase taxation upon citizens who have ignorantly assented to the destruction

taxation to real estate and incomes. “Many of the Prohibition States are bankrupt today because the fanatics fear that if their controlled legislatures increase taxation upon citizens who have ignorantly assented to the destruction  of lawful revenue, the whole fabric of deception will tumble down,” he wrote. He predicted that politicians kowtowing to the Prohibition “fanatics” would lose their jobs if taxation was visibly shifted.

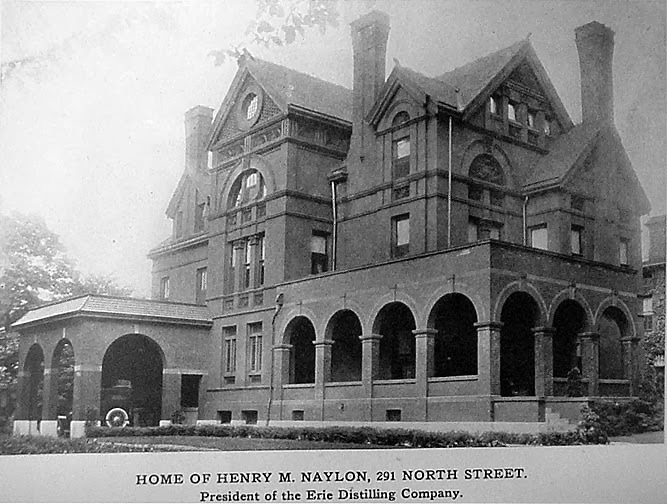

of lawful revenue, the whole fabric of deception will tumble down,” he wrote. He predicted that politicians kowtowing to the Prohibition “fanatics” would lose their jobs if taxation was visibly shifted.In 1903 Naylon bought a house, shown left, at 361 Pennsylvania Avenue in Buffalo. It had been designed and built in 1875 by an internationally known Philadelphia architect named Richard A. Waite who had made it his own home for many years. As Naylon’s millions accrued, however, the family decided a much larger and fancier house was required. The result was the mansion below on Buffalo’s then fashionable North Street. Son William, a bachelor, continued to live his with parents as part of the household.

Under Naylon’s leadership, the New York and Kentucky Company continued to pay dividends to its stockholders. Meanwhile its despised rival, the “Distillers & Cattle Feeders Trust,” was falling apart, reputedly because of its weight of debt and reputation for violence. As fast as the Trust shut down distilleries they sprang up elsewhere. Price fixing in the whiskey industry had proved to be elusive. In place of the Whiskey Trust a number of smaller, more regional combinations emerged. Meanwhile Naylon’s organization rolled on until its operations and those of its distilleries, including the Erie Distilling Company, were forced to shut down by National Prohibition.

Naylon emerged unfazed. He began to devote himself full-time to real estate, in which he previously had been an investor. His real estate empire grew extensively, with properties located throughout Buffalo and across New York State. The 1930 census found him, now age 60, living in his mansion with wife Nellie and son William. Naylon gave his occupation as “capitalist-real estate.” William was listed as “salesman - real estate.” The family was out of the whiskey business for good.

Henry Naylon died at age 69 in June 1939 and was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery located in the town of Tonawanda, a cemetery of the Catholic Diocese of Buffalo. Both Nellie and William had preceded Naylon in death, both passing in 1935. The Naylons lie together in a striking mausoleum, a hewed granite structure that today stands tall and solid in the graveyard. Meanwhile the Naylon mansion on North Street long since has been demolished to make way for new development.