Abraham Lincoln arrives at the Capitol in Washington, D.C., for his inauguration on March 4, 1861, seated in an open carriage next to President James Buchanan. (The Granger Collection, NY)

From the New York Times Disunion, "A Capital Under Slavery’s Shadow," by Adam Goodheart, on 24 February 2011 -- Newspapers announced that the sale would take place in one week’s time: on the very morning of Inauguration Day. At the precise hour that Abraham Lincoln rode down Pennsylvania Avenue to take his oath of office beneath the East Portico of the Capitol, a group of black people would stand beneath another columned portico just five miles away – at the Alexandria Courthouse.

“SHERIFF’S SALE OF FREE NEGROES,” the ad read. “On the 4th day of March, 1861 … I will proceed to sell at public auction, in front of the Court House door, for cash, all FREE NEGROES who have failed to pay their tax for the years 1859 and 1860.” It was a chilling reminder – in case any were needed – of the squalid realities lying almost literally in the shadow of the republic’s glittering monuments.

Ad in the Alexandria Gazette, Feb. 25, 1861.

The men and women in Alexandria were not being sold back into permanent bondage. They had fallen behind on paying the annual “head tax” that Virginia imposed on each of its adult free black inhabitants, and now their labor would be sold for as long as necessary to recoup the arrears. It is all too easy to imagine the deliberate humiliation thus inflicted on people who, in many cases, had spent long years in slavery before finally attaining their hard-won freedom. That scene at the courthouse door represented everything they had worked a lifetime to escape.

Across the Potomac, in the nation’s capital itself, slavery and racial injustice were daily realities too. The labor of black men and women made the engine of the city run. Enslaved cab drivers greeted newly arrived travelers at the city’s railway station and drove them to hotels, such as Gadsby’s and Willard’s, that were staffed largely by slaves. In local barbershops, it was almost exclusively black men – many of them slaves – who shaved the whiskers of lowly and mighty Washingtonians alike. (“The senator flops down in the seat,” one traveler noted with amusement, “and has his noble nose seized by the same fingers which the moment before were occupied by the person and chin of an unmistakable rowdy.”)

Washington free blacks being auctioned to pay jail fees, 1836. (Library of Congress)

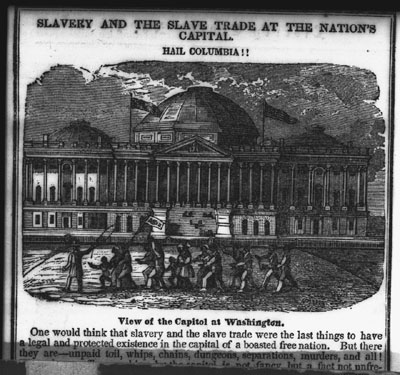

Enslaved laborers toiled at the expansion of the Capitol. Enslaved bodyservants attended their masters on the floor of the Senate, in the Supreme Court chamber – and sometimes even in the White House. No fewer than 10 of the first 15 presidents were slaveholders: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, James Polk and Zachary Taylor. (However, Washington never lived in Washington, D.C., and Van Buren and Harrison both freed their slaves long before taking office.)

Even the slave trade – although supposedly outlawed in Washington more than a decade earlier – still operated there quite openly, with black men and women frequently advertised for sale in the newspapers, and occasionally even sent to the auction block just a few hundred yards from the White House. The ban, passed as part of the Compromise of 1850, technically only forbade the importation of blacks into the District of Columbia to be sold out of state. The law permitted a local master to sell his or her own slaves – and there was little to keep them from being sent across the river to Alexandria, where slave trading flourished on an industrial scale, and the unfortunate captives might easily be forced aboard a cramped schooner bound for New Orleans or Mobile. Nor was it an uncommon sight to see a black woman going door-to-door in the most fashionable neighborhoods of Washington, begging for small donations toward buying her children out of slavery.

A slave coffle in Washington, D.C., possibly marching to auction, from William S. Dorr, Slave market of America, published by the American Anti-Slavery Society, 1836. Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-19705. The J. W. Neal slave house was near the city's center market (source: Southern Spaces)

Politicians from the free states – including the staunchest abolitionists – were constantly reminded here that slavery was no mere theoretical abstraction. Indeed, they found themselves immersed in slavery’s presence from the moment they arrived in the capital. In February 1861, this was true of the newly arrived president-elect. Lincoln was very conscious of the fact that he was taking up residence in slave territory – indeed, in a city just as Southern in many respects as Richmond or Nashville.

On Feb. 27, Lincoln gave his first public speech in Washington, addressing a group of local dignitaries in a parlor at Willard’s – a hotel with many enslaved workers. He spoke as if he were a foreign head of state visiting some alien capital:

As it is the first time in my life, since the present phase of politics has presented itself in this country, that I have said anything publicly within a region of the country where the institution of slavery exists, I will take this occasion to say, that I think very much of the ill feeling that has existed and still exists between the people of the section whence I came and the people here, is owing to a misunderstanding between each other which unhappily prevails. … I hope, in a word, when we shall become better acquainted – and I say it with great confidence – we shall like each other the more.

Two days later, when Lincoln addressed a larger crowd gathered outside the hotel, he struck a similar note, telling his listeners that he hoped to “convince you, and the people of your section of the country, that we regard you as in all things being our equals.” He assured them he harbored no plans to “deprive you of any of your rights under the constitution of the United States” – an obvious reference to their supposed right to hold slaves.

Lincoln had lived with slavery here before, as a one-term member of Congress in the late 1840s. He and his wife had rented rooms in a boardinghouse owned by a Virginia-born lady, Ann Sprigg, who employed several hired slaves. (Despite this, Sprigg’s was known as “the Abolition house” for the political leanings of its occupants.) At that time, slavery’s worst atrocities were even more visible in Washington than they would be in 1861: Coffles of slaves, shackled to one another in straggling single file, were marched past the Capitol on their way to Southern markets. In 1848, slave traders kidnapped Henry Wilson, an enslaved waiter at Sprigg’s – a man whom Lincoln probably knew well.

In fact, Congressman Lincoln was so appalled by his experiences that in January 1849 he introduced a bill to completely – albeit gradually – abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. The law would have provided compensation to masters for emancipating their slaves, a scheme similar to the one eventually implemented in Washington (and attempted in Delaware) during Lincoln’s presidency. The proposal was a topic of lively conversation at Sprigg’s boardinghouse. “Our whole mess remained in the dining-room after tea, and conversed upon the subject of Mr. Lincoln’s bill to abolish slavery,” one congressman wrote in his diary. “It was approved by all; I believe it as good a bill as we could get at this time.”

The proposal went nowhere in Congress. When President-elect Lincoln returned to Washington in 1861 after a 12-year absence, all too little had changed. During the first week of March, the same local newspapers carrying reports on his inauguration also ran an ad from a Louisiana cotton planter, who announced that he was in town to purchase several dozen healthy slaves. “Any person having such to dispose of,” the planter added, might write to him care of the District of Columbia post office.

What remained to be seen was whether the new president would maintain the vows he made at Willard’s. Would he leave Washington just as he had found it: the capital city of a slave republic? Or would the principles that an obscure Illinois congressman had espoused in the dining room of Mrs. Sprigg’s “Abolition house” reemerge, in more potent form, once he was in the White House? (source: New York Times Disunion)