That's according to findings from University of Cincinnati research at Pompeii to be presented Jan. 7, 2012, at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America by UC doctoral student Allison Emmerson. She has worked on site as part of UC's Pompeii Archaeological Research Project.

New research counters long-held assumptions

Emmerson's research counters long-held assumptions about how and why tombs around Pompeii have been found piled high with ancient trash deposits in and around the structures, including butchered and charred animal bones, dog and equine bones, broken pottery and broken architectural material. These garbage materials in cemeteries were found within and alongside tomb structures, even those of one story which were preserved nearly as they existed in AD 79 because of the thick, hardened coating of ash and lapilli (small stones) that covered and preserved them due to the AD 79 eruption of Vesuvius.

The 19th century excavators at Pompeii assumed that the excavated tombs filled with ancient refuse and garbage (as well as covered in graffiti) must have fallen into decline and disrepair almost two decades prior to the AD 79 catastrophic eruption of Vesuvius. They (and later excavators) theorized that Pompeii's tombs were covered in garbage due, in part, to a powerful AD 62 earthquake at Pompeii and that the tombs were abandoned and neglected after the earthquake as the city must have been in decline and inhabitants focused on more pragmatic concerns.

|

| Tomb at Pompeii with graffiti painted in red. Ancient garbage was found surrounding this tomb [Credit: Allison Emmerson, University of Cincinnati] |

However, recent scholarship of the last 15 years or so has proven that Pompeii had rebounded after the earthquake of AD 62 and was in a period of rejuvenation by AD 79 as an important city in one of the wealthiest regions of the Roman Empire.

"Which," according to UC's Emmerson, "Left the question of why so much trash was found in the cemeteries. These were not abandoned locales as of AD 79 . People had not abandoned the maintenance of their burial spaces and structures any more than they had abandoned public spaces."

The Ancients held a casual view of trash collection

As Emmerson began excavations at Pompeii in 2009, as part of a long-term team of UC faculty and students working there, she noted the placement of Pompeii's tombs – located not in secluded park-like areas set off by a fence (as are our cemeteries today) but prominently placed along well-used, high-traffic roads and thoroughfares of the time.

She also noted what we would consider an extremely "casual" treatment of trash and waste.

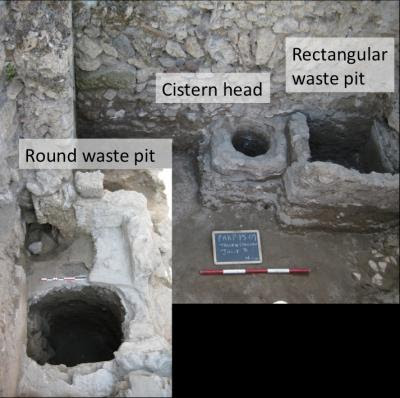

"For instance," she explained, "I excavated a room in a house where the cistern (for storing drinking water and water for washing) was placed between two waste pits. Both waste pits were found completely packed with trash in the form of broken household pottery, animal bones and other food waste, like grape seeds and olive pits."

In addition, researchers have commonly found that garbage was casually deposited on the floor of homes, in the streets and alleys outside of homes (sometimes at significant layered depths) and at the urban edge, along city walls (in large quantities over time).

In fact, there is no evidence that Pompeii had any centrally managed system for garbage disposal, and so, it's likely people lived in very close proximity to their refuse as an accepted part of life.

And Pompeii's cemeteries and tombs were simply another place for trash – as were almost any part of a home's interior or exterior as well as alleys, streets and major roadways.

Tombs and cemeteries were certainly considered appropriate for the placement of "advertisements" of the time, everything from political "vote for me" material, promotions for sporting events or boasts of sexual conquest.

"In general, when a Roman was confronted with death, he or she was more concerned with memory than with the afterlife. Individuals wanted to be remembered, and the way to do that was a big tomb in a high-traffic area. In other words, these tombs and cemeteries were never meant to be places for quiet contemplation. Tombs were display – very much a part of every day life, definitely not set apart, clean or quiet. They were part of the 'down and dirty' in life."

When it comes to why so much trash is found at tombs at Pompeii, Emmerson added that her research findings contrast with the theories of early excavators at Pompeii because those first excavators couldn't conceive of trash placed at tombs as just a normal part of everyday life since its was so foreign to their (and our own) value systems. It seems, she said, so disrespectful by modern standards; however, evidence within the walls of Pompeii shows that the people lived close to their waste, and we can't be sure that trash in tombs would have been seen as a problem.

"And frankly," she added, "The early excavators at Pompeii just weren't that interested in the trash and what it might tell us about daily life and cultural attitudes."

Source: University of Cincinnati [January 04, 2011]