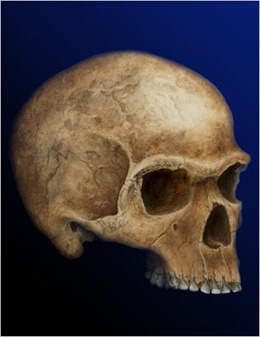

Longevity in early modern humans and in Neanderthals was about the same, according to a new study, suggesting that long life was not what helped the population of early modern humans increase.

Erik Trinkaus, an anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis and the study’s author, reported his findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Erik Trinkaus, an anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis and the study’s author, reported his findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“There must have been something else happening because the populations of early modern humans were expanding,” he said. “The last Neanderthal we know of lived about 40,000 years ago.”

Dr. Trinkaus studied fossil records of humans from across Eurasia and of Neanderthals from the western half of Eurasia to estimate adult mortality in the two groups. He found that there was approximately the same number of adults in the 20-to-40 age range and over-40 age range in both groups. About 25 percent of adult humans and Neanderthals survived past 40.

With longevity being equal, scientists may need to better understand fertility rates and infant mortality rates to determine why human populations expanded and thrived while Neanderthals dwindled to extinction.

“It means that we need to look for the reasons elsewhere, of which survival rates for children may be one answer,” Dr. Trinkaus said.

The research also brings up other interesting questions about how humans passed on knowledge over the years, said Julien Riel-Salvatore, an anthropologist at the University of Colorado, Denver.

“The oldest people have more life experience and the largest body of knowledge,” he said. “So was there an increased reliance on symbolic artifacts, on ornaments and paintings?”

Author: Sindya Bhanoo | Source: The New York Times [January 10, 2011]