Clues to the group's disappearance are found in layers of volcanic ash in a cave in the northern Caucasus Mountains that preserve a long record of Neanderthal occupation preceding those layers and none afterward.

A cave in the northern Caucasus Mountains may hold a key to the long-standing mystery of why the Neanderthals, our closest relatives, went extinct.

A cave in the northern Caucasus Mountains may hold a key to the long-standing mystery of why the Neanderthals, our closest relatives, went extinct.

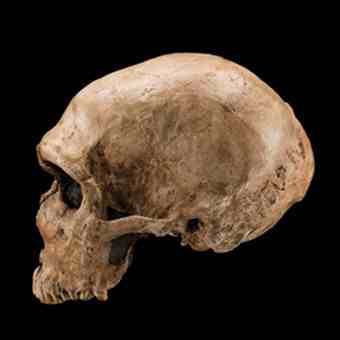

For nearly 300,000 years the heavy-browed, barrel-chested Neanderthals presided over Eurasia, weathering glacial conditions more severe than any our own kind has ever faced.

Then, starting around 40,000 years ago, their numbers began to decline. Shortly after 28,000 years ago, they were gone.

Paleoanthropologists have been debating whether competition with incoming modern humans or the onset of rapidly oscillating climate was to blame for their demise.

But new findings suggest that catastrophic volcanic eruptions may have doomed the Neanderthals — and paved the way for modern humans to take their place.

Researchers led by Liubov Vitaliena Golovanova of the ANO Laboratory of Prehistory in Saint Petersburg studied the deposits in Mezmaiskaya cave, located in southwestern Russia.

First discovered by archaeologists in 1987, the cave once sheltered Neanderthals and, later, modern humans. Analyzing the various stratigraphic layers, the scientists f

ound layers of volcanic ash that, based on the geochemical composition of the ashes, they attribute to eruptions that occurred in the Caucasus region around 40,000 years ago.

Because the cave preserves a long record of Neandertal occupation preceding the ash layers but no traces of them afterward, the team surmises that the eruptions devastated the locals.

Moreover, looking more broadly at sites across Eurasia, the investigators noted that the eruptions coincided with the disappearance of the Neanderthals across most of their range, save for a few groups that took refuge in the south.

In a paper published in Current Anthropology, they propose that the eruptions precipitated a so-called volcanic winter that may have resulted in mass deaths of Neanderthals and their prey.

The misfortune of the Neanderthals, however, was a boon for modern humans, who lived in southern locales unaffected by the volcanic activity.

Once the Neanderthals were gone, so the theory goes, moderns could move north unchallenged.

The team’s interpretation of the data from the cave has elicited criticism from some researchers, such as Francesco G. Fedele of the University of Naples in Italy, who complained in commentaries published alongside the paper that the age of the ashes is not firm enough to draw such conclusions.

But others, including Paul B. Pettitt of the University of Sheffield in England, called the new extinction and replacement scenario plausible.

The riddle of the Neanderthals’ downfall is far from solved, but the volcanic eruption theory may turn up the heat on the competition.

Author: Kate Wong | Source: Scientific American [December 07, 2010]