Where is Atlantis? Ever since Plato mentioned the existence of the fabled island-city in the 4th century BC, archaeologists, historians and adventurers have spent much time and ink trying to chase down its origins.

“Now in this island of Atlantis there was a great and wonderful empire which had rule over the whole island and several others, as well as over parts of the continent, and, besides these, subjected the parts of Libya within the columns of Heracles as far as Egypt, and of Europe as far as Tyrrhenia.” – From Plato’s Timaeus – Translation by Benjamin Jowett

“Now in this island of Atlantis there was a great and wonderful empire which had rule over the whole island and several others, as well as over parts of the continent, and, besides these, subjected the parts of Libya within the columns of Heracles as far as Egypt, and of Europe as far as Tyrrhenia.” – From Plato’s Timaeus – Translation by Benjamin Jowett

One of the suggested locations of Atlantis is the island of Crete, just off the Greek coast. In around 2000 BC it was home to the Minoans. Sir Arthur Evans, one of the first people to excavate the civilization, named the Bronze Age civilization after King Minos, a mythical king who is said to have ruled from Crete in ancient times.

Most of what we know about the Minoans comes from the architecture and artefacts they left behind. While they were a literate people, the script they produced, which archaeologists call Linear A, remains un-deciphered.

The Minoans did not rise in isolation. In circa 2000 BC the Egyptians were re-unifying into their Middle Kingdom period. At the same time, in Mesopotamia, the Assyrians were growing into a massive state.

Not an Empire of Land...

If Atlantis was indeed the city of the Minoans, then Plato had a really inflated idea of their military prowess. There is little evidence that the Minoans controlled more territory than Crete and some nearby islands. They never conquered Egypt or controlled large sections of Europe, as the people of Atlantis are said to have done.

In fact, Sir Arthur Evans was unimpressed by the lack of Minoan fortifications and deduced that they were a peaceful people who lived in a sort of “pax Minoica.” Today we know that they were interested in military affairs. There are fortifications on Crete, including some just-discovered walls at Gournia.

In fact, Sir Arthur Evans was unimpressed by the lack of Minoan fortifications and deduced that they were a peaceful people who lived in a sort of “pax Minoica.” Today we know that they were interested in military affairs. There are fortifications on Crete, including some just-discovered walls at Gournia.

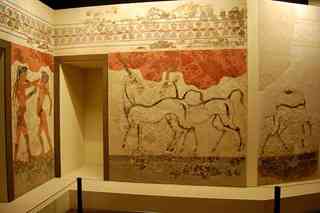

Also on Santorini, a nearby island that came under Minoan influence, there is a fresco that shows a large fleet near its shores. It’s been hypothesized that this fleet was meant to be used in warfare.

The Minoans did have an interest in warfare – but were not able (or not willing) to capture territory outside of the Aegean.

... but a Land of Trade and Art

While the Minoans were not great conquerors the evidence at hand indicates that they were good traders.

We know that they traded with Egypt, the Near East and mainland Greece. Indeed the town of Gournia – on the north coast – had facilities for bronze-working and wine making. It also had a substantial ship-shed (harbor) that berthed vessels coming to and leaving the island. A recent find at the site of Raos, also on Santorini, shows that they even traded in gold.

Minoan art is also well known. The palace at Knossos contains numerous frescoes depicting dolphins, rosettes and of course the famous bull-leaping scenes.

Minoan art is also well known. The palace at Knossos contains numerous frescoes depicting dolphins, rosettes and of course the famous bull-leaping scenes.

Bull-leaping appears to have played a particularly important role in Minoan art. Professor Maria Shaw said that Knossos is the only site on Crete where these depictions are shown. “I stress in no other palaces,” she said. This indicates that the people at Knossos had a monopoly of sorts on that image – a sign of the power of that place.

Minoan art was also highly regarded in Egypt. At the site of Tell el-Dab’a, on the Nile Delta, Minoan frescoes have been found in the palace-complex used by the pharaoh. It’s a source of debate how they got there, with one idea being that unemployed Minoan artists came to Egypt and were granted the right to work there.

An Empire Struck by Disaster

“There occurred violent earthquakes and floods; and in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared, and was sunk beneath the sea...” – From Plato’s Timaeus (Translation by Benjamin Jowett).

There is a chapter in Minoan history that sounds eerily similar to this.

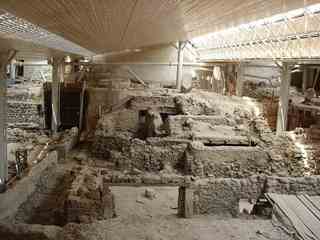

On Santorini there was a city known as Akrotiri. Like Knossos it had many frescoes. The depictions include two boys boxing, a fisherman holding his catch and a fleet of vessels near the island – perhaps returning from a military strike.

This society flourished until some point in the late 17th century BC when Akrotiri was devastated by a series of earthquakes, causing its citizens to flee. Shortly after that a volcano on the island exploded, burying Akrotiri forever – no substantial settlement existed on the island for the rest of the Bronze Age.

This society flourished until some point in the late 17th century BC when Akrotiri was devastated by a series of earthquakes, causing its citizens to flee. Shortly after that a volcano on the island exploded, burying Akrotiri forever – no substantial settlement existed on the island for the rest of the Bronze Age.

How much damage this eruption did to Crete itself is debated. Recent research suggests that a huge tsunami wrecked havoc on the coastline.

“We’re talking about an extreme event, certainly on the order of the 2004 Indian Ocean disaster,” said Dr. Costas Synolakis, of the University of Southern California, in a 2008 Discover Magazine article.

Now, here is where Crete breaks away from the Atlantis legend. Archaeologists can say that Minoan civilization did not end in the late 17th century BC. Instead it staggered on for nearly 150 years, until the final destruction of the Palace of Knossos in the mid 15th century BC.

It took an invasion by a people called the Mycenaeans to put an end to it. These Greek speaking people landed on Crete and swept over the island, colonizing it. At Gournia, the fortifications the inhabitants built on the beach turned out to be useless - the Mycenaean people by-passed them by attacking overland. "Many other settlements were destroyed at the same time. My guess is that they just came along the land; they didn’t have to come up from the sea,” said Professor Vance Watrous, who co-discovered the fortifications.

Chasing Atlantis

So how does the idea that the Minoans lived in Atlantis stand up among scholars? Generally it doesn’t fare very well. You will be hard pressed to find recent scholarship that supports the idea.

Gerrard Naddaf wrote in the journal Phoenix that “the vast majority of classical scholars take the story to be what Plato explicitly denies it to be: invented myth.”

He points to several problems in equating the Minoans with Atlantis. The island is said to have existed nearly 9,000 years before Plato’s time – yet we know that the Minoans vanished only 1,000 years before his life.

Why would Plato be so far off? “To argue that this is so because the Greeks had a poor notion of time is hardly serious.” Geography is another problem, Atlantis is supposed to be beyond the “pillar of Hercules” – in other words, in the Atlantic Ocean. Crete, on the other hand, is not far from the Greek coast.

Classicist John Victor Luce wrote in Classics Ireland that we shouldn’t be trying to identify archaeology ruins as Atlantis. The legendary island is “more properly a matter for literary criticism, that is, or should be, centred in the study of Plato’s Timaeus and Critias,” he said.

However Luce said that earlier generations of classicists were more willing to consider the idea of the Minoans being the inspiration for Atlantis. He said that the idea was first raised in 1909 by a scholar named K.T. Frost, a professor at Queens University Belfast. He wrote an anonymous letter to the Times presenting the idea.

He wrote that - “If Plato’s story was an invention, however, we need not assume that it was a pure creation of his fancy. He might work into it anything that he had heard or read of earlier civilizations and dominions existing within the circuit of the Hellenic world.”

Source: Heritage-Key