Pharaoh Akhenaten (r. 1353-1336 B.C.) dedicated his 17-year reign and the resources of New Kingdom Egypt to the exclusive worship of the Aten or solar disk, profoundly affecting the history of his polytheistic civilization's art. In the enigmatic ruler's remote capital Akhetaten (present-day el-Amarna), the chief royal sculptor Thutmose and his workshop produced female images of remarkable beauty and startling naturalism. Each was a radical departure from the centuries-old static and idealized representations of the human body.

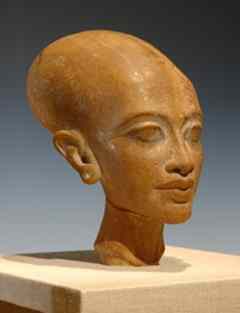

One such graceful work, the Sculpted Head of a Princess from Amarna (ca. 1340-1337 B.C.), is on view in the special exhibition Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs.

Thutmose and Composite Sculpture

Upon the heretic Akhenaten's death, his successor Tutankhamun (r. 1332-1323 B.C.) returned to Memphis or Thebes with Akhetaten's populace. Under the boy-king's rule, polytheism and traditional forms of art were restored. Taking only what was necessary with them, the visionary Akhenaten's sculptors left behind a rich deposit of unfinished Amarna Period works.

The remaining objects from Thutmose's highly organized studios at Akhetaten, examples of negative selection, were excavated by German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt and his team in 1912. Among them were the unfinished painted portrait Bust of Nefertiti, Akhenaten's principal wife, and sculpted heads of young females.

Thutmose's workshop excelled in the production of composite sculpture. Various artisans were assigned the task of fabricating a statue's head, torso, arms, legs, wig and headdress. The separate parts, often from different kinds of colored stone, were intended for assembly into a complete statue. This division of labor, unusual in ancient times, accelerated the production of royal images for the decoration of Akhenaten's palaces and open-air temples.

Head of an Amarna Princess

Borchardt's excavations at the site of el-Amarna yielded a number of quartzite heads. Three are presumably busts of Akhenaten's daughters. Two reside in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. The third one, highly polished, is housed in Berlin's recently refurbished Neues Museum.

Unearthed from Thutmose's studio, the beautifully modeled Sculpted Head of a Princess from Amarna was carved from light brown quartzite to imitate the Egyptian female skin tone. Perhaps a likeness of Meritaten, Akhenaten and Nefertiti's eldest daughter, the tenon or dowel at its base indicates that the approximately two-thirds life-sized bust was intended for insertion into a composite sculpture.

The black pigment outlines of its almond-shaped eyes and eyebrows mark spaces reserved for inlays of favored stone. The bareheaded sculpture was broken at its long neck and rejoined in antiquity. Scholars continue to speculate about the pronounced elongation of the broad head's skull. Some attribute its unusual shape to a cranial abnormality.

A characteristic of Amarna royal portraiture, the bust's overtly ovoid appearance possibly refers to Pharaoh Akhenaten's perception of the egg as a symbol of creation and life's divine origin.

In the Post-Amarna Period, similar imagery occurs in a painted wooden bust of Tutankhamun portrayed as the infant sun god on a lotus. The work, discovered by archaeologist Howard Carter in the entrance passage to the boy-king's modest tomb, bears witness to Akhenaten's ideological and artistic legacy.

Source: Art Museum Journal