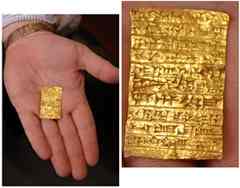

An ancient gold tablet unearthed in a 1913 dig in modern-day Iraq that mysteriously ended up in the possession of a Holocaust survivor will remain in his estate, a surrogate has ruled, rather than be returned to a German museum.

In a ruling that reads like a script for an Indiana Jones movie, Nassau County, N.Y., Surrogate John B. Riordan held that the Berlin museum, where the tablet had been kept for 19 years before its sudden disappearance at the end of World War II, could not stake a claim to the artifact as it had not acted promptly to recover it.

In a ruling that reads like a script for an Indiana Jones movie, Nassau County, N.Y., Surrogate John B. Riordan held that the Berlin museum, where the tablet had been kept for 19 years before its sudden disappearance at the end of World War II, could not stake a claim to the artifact as it had not acted promptly to recover it.

"The court finds that the museum's lack of due diligence was unreasonable," Surrogate Riordan wrote in Matter of Flamenbaum, File No. 328416, in holding that the museum's claim was barred by the doctrine of laches.

The gold tablet was found during an excavation around the city of Ashur, now Qual'at Serouat, Iraq, by a team of German archeologists led by Walter Andrae. The inscribed tablet, which was discovered in the foundation of the Ishta Temple, is actually a construction document, according to the judge. It dates to the reign of the Assyrian King Tukulti-Ninurta I (1243-1207 BCE) who expanded the Assyrian empire but was later killed by his son.

When the excavations finished in 1914, the tablet was packed up along with other artifacts and sent to Basra, where it was loaded on a Germany-bound freighter. The outbreak of World War I forced the ship to change course to Portugal where the artifacts were stored until 1926, when they finally arrived in Berlin.

In 1934, the tablet was put on display at the Vorderasiatisches Museum, known for its collection of Southwest Asian art. Five years later, with World War II looming, the museum was closed and the tablet was put in storage along with other antiques and works of art. At the end of the war in 1945, an inventory discovered that the tablet was missing.

Nearly 60 years later, in April 2003, the tablet was discovered among the possessions of Riven Flamenbaum, of Great Neck, N.Y., after his death at the age of 92. Flamenbaum left behind three children, Israel, Hannah and Helen. In a 1971 will, he left the tablet to his three children, said Steven Schlesinger, the attorney who represented Hannah, the executor of the estate.

In May 2006, Israel notified the German museum that his father's estate had the tablet. The museum then sought its return.

At a Surrogate Court hearing in September 2009, the director of the museum, Beate Salje, testified that Russian troops had taken valuables from the museum at the end of World War II and had returned some but not all of the objects in 1957. Salje told the court that the museum had no record of the items taken, but the tablet may have been among them.

Schlesinger argued that under the "spoils of war" doctrine, cultural property removed by Russian troops during the occupation of Berlin after World War II was "lawfully transferred from one sovereign to another and that this taking of the gold tablet extinguished the rights of the museum pursuant to international law."

The estate also contended that the museum's claim was barred by laches as it had waited too long to pursue its stake in the tablet. It pointed out that the museum had never reported the tablet as stolen and had never listed it as missing on any international art registry, even after a University of Chicago professor reported that he had seen the artifact in New York.

The museum countered that both international authorities and the Hague Convention of 1907 prohibit "pillaging and plundering."

The museum's director testified that in post-war Berlin, it "just didn't make sense" to fill out a report or alert the authorities, given the chaotic nature of the occupation and the separation of East and West Berlin.

As the museum was located in East Berlin, a "Soviet satellite state," the political and financial restraints imposed on it made its delay "entirely reasonable," the museum argued in court papers. At trial, Salje also said the expectation at the time was that the Russians would return every artifact after the occupation ended.

DILIGENCE QUESTIONED

Surrogate Riordan acknowledged that the museum had complied with the statute of limitations by filing its replevin claim within three years after the estate rejected its demand to return the tablet. However, he pointed out that, even where a statute of limitations has not run, an owner's claim still may be defeated by the doctrine of laches.

Under New York law, the original owner may not be "lax in searching for missing or stolen property or…delay unreasonably in making a demand," Surrogate Riordan wrote. "The owner must be diligent, because even where the statute of limitations has not run, the claim may be barred by the doctrine of laches."

The surrogate noted the museum's admission that the disappearance of the tablet was only noted in the museum's internal records and that no efforts were made to recover it after the uncorroborated 1954 report of its location.

The museum's "inexplicable failure to report the tablet as stolen, or take any other steps toward recovery" resulted in no notice of a "blemish in the title" to the tablet's owners over the last 60 years, the court concluded.

Surrogate Riordan characterized the theory that Russians had taken the tablet as "largely circumstantial" and not "above the level of conjecture." Moreover, he said that Flamenbaum's death had "forever foreclosed his ability to testify as to when and where he obtained the tablet," thus prejudicing the estate's ability to defend against the museum's claim.

"These are precisely the circumstances in which the doctrine of laches must be applied," the court concluded.

Hannah Flamenbaum, an assistant New York attorney general, said that after surviving Auschwitz her Polish-born father came to the United State in 1949 and worked in a liquor store on New York City's Canal Street, which he eventually bought and ran.

"I told the court, our understanding was that he got it from the Russians on the black market," said Schlesinger, of Jaspan Schlesinger in Garden City, N.Y. "That was what he had always told his children."

Schlesinger said there had been six tablets in the world like the one acquired by the estate, but that two had disappeared.

Flamenbaum said the family would like to keep the artifact. "It represents my father's hardships," she said.

John C. Fisher of Hamburger, Weinschenk & Fisher in Manhattan represented the museum. He could not be reached for comment.

Source: Law.com